February 04, 2016

School Counselor Week: Access to School Counselors in PA Schools

Download a PDF of the issue brief

K-12 School Counselors

K-12 school counselors work in elementary, middle, and high schools to help improve student cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes such as grades, enrollment in challenging courses, socio-emotional health, personal development, and college- and career-readiness, including enrollment in post-secondary institutions of education.[1] They also promote equity in student outcomes and assist in the development of healthy and supportive school climates.[2] Indeed, a growing body of research concludes school counselors are crucial to student outcomes, including both socio-emotional health and academic success.

While the primary duties of counselors involve working directly with students, many counselors also serve as testing coordinators and perform other additional duties that have historically not been associated with the job of counselor.[3] Unfortunately, these additional roles dilute the amount of time counselors can spend with individual students in the role of counselor. Further, the rapid increase in the number of economically disadvantaged students and the number of students desirous of entering post-secondary education have also placed additional demands on the time and attention of counselors.

For school counselors to effectively assist students, the American Association of School Counselors recommends a maximum ratio of 250 students for every full-time counselor. Moreover, research suggests that reducing the student-counselor ratio has positive effects on a variety of student outcomes[4].

In this brief, we examine student access to school counselors by analyzing the schools that have school counselors and the ratio of students to counselors in schools. Before reviewing the results of our study, we provide a brief review of the research that has established the impact of counselors on various student outcomes.

Do School Counselors Matter?

Looking back on our experiences in school, many of us know the answer to that question is a definitive Yes! Further, as we review below, research has consistently shown that counselors can have a positive impact on a variety of student outcomes, including both cognitive and non-cognitive.

Impact on Academic Outcomes

Counselors can play a pivotal role in reducing dropout rates and preventing absenteeism–especially at the high school level and in high-poverty schools. Counselors accomplish this by providing social support; monitoring and mentoring students; developing personal and social skills; and, involving teachers, administrators, and parents throughout the process.[5] Counselors also impact both access to and success in advanced coursework such as AP classes.[6] For example, Black students who participated in a well-designed counseling program performed better than those who did not participate, and they also outperformed the national norms for Black students taking the AP exam such that the results were comparable to their White peers.[7] Indeed, academic support programs and services offered by school counselors for students from historically under-performing groups can help create more equitable outcomes in schools.[8]

Impact on College and Career Readiness

The impact of school counselors on students is most visible when looking at the support provided to students most frequently visiting counselors, and the effect counselors have in relation to students meeting career and college aspirations.

Several variables affect career- and college-readiness: low student-to-counselor ratios, amount of time spent in contact with school counselors, time in contact with counselors early in high school, parental contact with counselors, and the number of school counselors available.[9] The educational and postsecondary aspirations held by counselors for their students are crucial to students seeking information related to college, especially in schools serving high poverty populations.[10]

Moreover, counselors have a more profound effect on college entrance rates when counselors start working with students early in their high school careers.[11] Finally, counselors are most crucial to the college aspirations of female and Black students, as research has found these sub-populations of students rely most heavily on the assistance of counselors.[12]

Impact on Socio-Emotional Outcomes

Importantly, counselors also attend to students’ non-academic needs. Counselors, for example, help to address the social, emotional, and personal factors that may impede a students’ academic success, sometimes through the use of developmental transition interventions.[13] The issues addressed by counselors can include students’ feelings of belonging, academic and educational aspirations, self-efficacy, and social as well as academic identities, especially for racial/ethnic minority students.[14],[15] These efforts, in turn, can assist in the development of a more positive school climate, particularly for racial/ethnic minority students.[16],[17]

Student-to-Counselor Ratio

Smaller student-to-counselor ratios are strongly correlated with schools having positive student outcomes, such as greater graduation rates and lower disciplinary incidents—especially in high-poverty schools—as well as greater college application rates.[18],[19],[20],[21]

While there is little research on student-counselor ratios, the available research generally evidences that the recommended ratio is largely ignored.[22] Indeed, ratios of 1000:1 are not all that uncommon.[23]

Study Methods

In this section, we present findings about two outcomes: schools employing a school counselor and meeting the recommended student-counselor ratio of 250:1. We used publicly available data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education[24] to create a data set that included counselor information from 2014-15 for schools receiving a state accountability rating.

We used simple inferential statistics to examine differences across schools and employed logistic regression analysis to identify the influence of school characteristics on the odds of: (a) employing a school counselor and (b) meting the recommended 250:1 ratio. We performed analyses separately for the three school levels. For more information about the data and methods we used, please contact Dr. Fuller at ejf20@psu.edu

Study Findings

We report statistically significant findings separately for: (a) the existence of a counselor (part- or full-time) in the school; and, (b) having a 250:1 or smaller student to counselor ratio.

Percentage of Schools with a Counselor

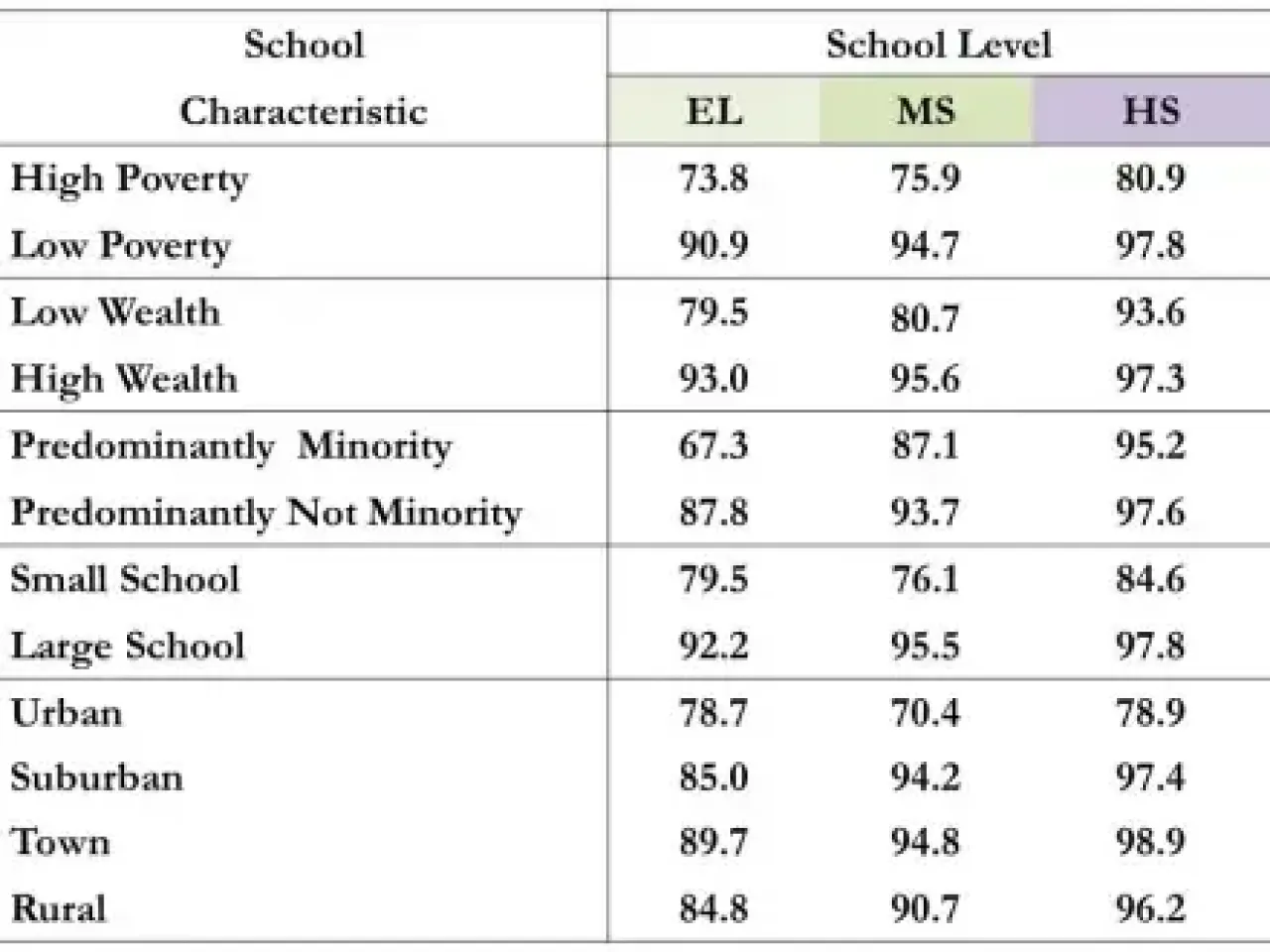

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of economically disadvantaged students and percentage of minority students are associated with the two outcome measures. Specifically, a substantially smaller percentage of high-poverty schools employed a counselor as compared to low-poverty schools. At all three school levels, the difference was at least 15 percentage points. Similarly, a significantly lower percentage of predominantly minority schools employed a school counselor as compared to not predominantly minority schools. The difference was particularly large at the elementary school—a difference of greater than 20 percentage points. Surprisingly, the difference was quite small at the high school level.

With respect to district wealth as measured by the state’s MVPI measure[25], a lower percentage of schools located in low wealth districts employed a counselor as compared to schools in high wealth districts. The differences, however, were not as large as in the poverty comparison.

A statistically smaller percentage of small schools employed a counselor as compared to large schools, and the differences were about 10 percentage points for each school level.

Finally, a significantly lower percentage of elementary urban schools employed a counselor as compared to schools located in towns while a significantly lower percentage of urban middle and high schools employed a counselor as compared to schools located in suburbs, towns, and rural areas.

Table 1: Percentage of Schools Employing a Counselor

In the logistic regression results, we simultaneously examine the impact of student characteristics, school size, and geographic location on the odds that a school employs a counselor. At all three levels, we found that school size was positively related to the employment of a counselor—meaning, as school enrollment increases, the odds of employing a counselor increases as well.

At the elementary- and middle- school levels, the percentage of Black students was negatively related to the employment of a counselor—meaning, schools with at least 70% Black students were about 69% less likely than other schools to employ a counselor.

At both the middle- and high-school levels, urban schools were less likely to employ a counselor than suburban schools. Specifically, urban middle schools were about 70% less likely to employ a counselor than suburban middle schools while urban high schools were about 74% less likely than suburban high schools to employ a counselor.

At the elementary school level, the greater the percentage of economically disadvantaged students, the lower the odds of employing a school counselor. Alternatively, schools located in urban districts and town districts were more likely to employ a counselor as compared to suburban districts. Specifically, urban and town schools were about 70% more likely to employ a counselor than suburban schools.

Percent of Schools Meeting the 250:1 Recommendation

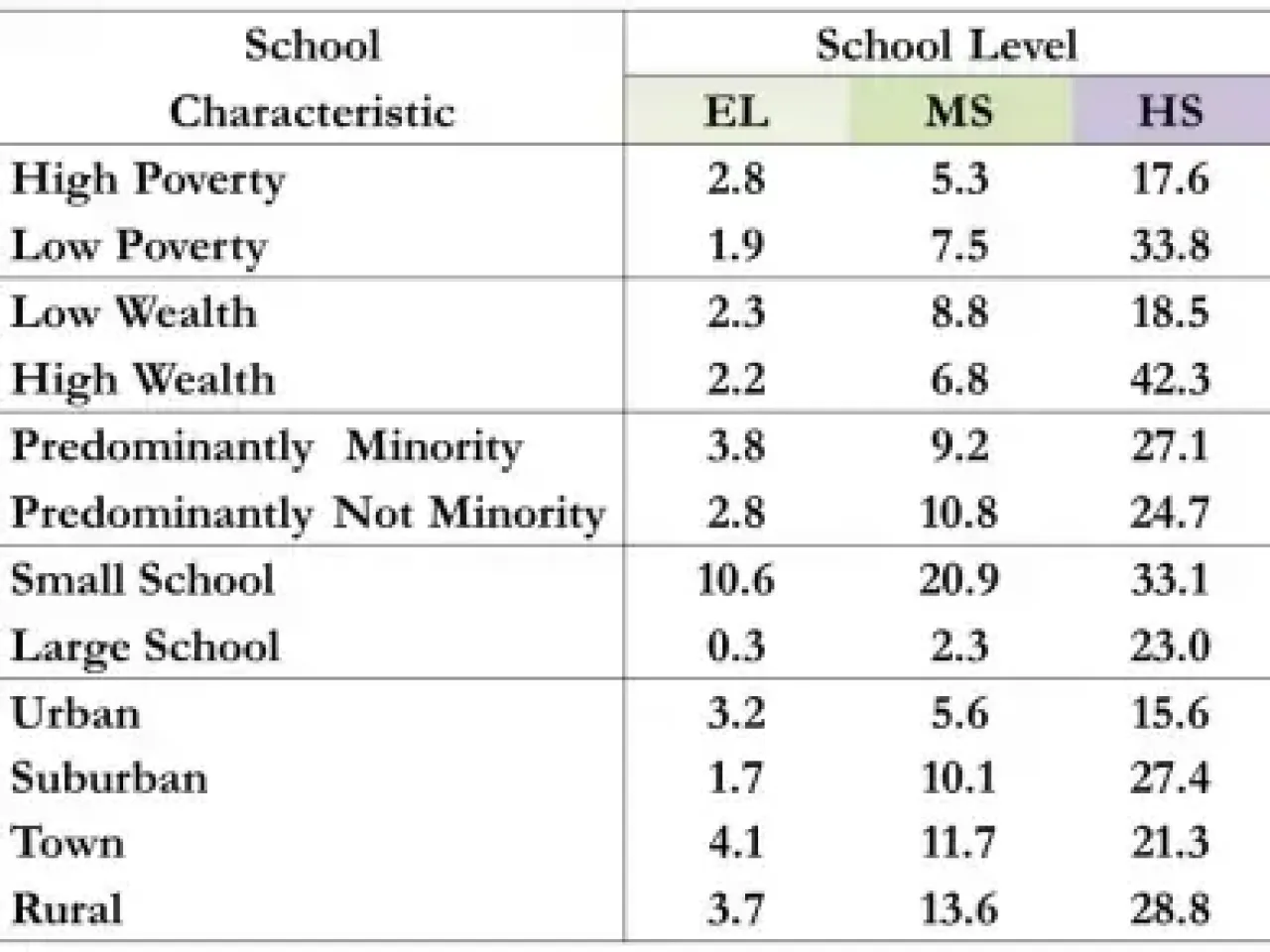

As shown in Table 2, the only noteworthy differences in the percentages of schools meeting the 250:1 ratio, again recommended by the American Association of School Counselors, were with respect to school size and geographic location. More specifically, a far greater percentage of small schools met the recommended ratio as compared to large schools. With respect to geographic locale, a lower percentage of urban schools met the recommended ratio than schools in the other three locales.

At the high school level, a greater percentage of low poverty and high wealth schools met the recommended ratio as compared to high poverty and low wealth schools, respectively. Indeed, the percentages for low poverty and high wealth schools were at least double the percentages for high poverty and low wealth schools.

While there was not a substantial difference in the percentages for predominantly and not predominantly minority schools, there were differences with respect to school size and geographic location. Specifically, a greater percentage of small schools than large schools met the recommended ratio, while a lower percentage of urban schools than suburban, town, or rural schools met the recommended ratio.

Table 2: Percentage of Schools Meeting 250:1 Student to Counselor Recommendation

Given the small percentages and fairly inconsequential differences for elementary and middle schools, our logistic regression analysis focused only on high schools. We found that the greater the percentage of economically disadvantaged students enrolled in the school, the lower the odds that the school met the recommended ratio. We also found that an increase in the percentage of special education students in a school was associated with an increase in the odds the school met the recommended ratio. Finally, we found that an increase in school size was also positively associated with meeting the recommended 250:1 ratio.

Conclusions

While research suggests that counselors may have their greatest impact on poor and minority students, our research examining access to counselors in Pennsylvania public schools reveals the students most in need of assistance from counselors, and who would benefit most from the support of counselors, are the least likely to have access to counselors. Indeed, students enrolled in high-poverty and predominantly minority were generally less likely to have a counselor employed in the school and, if there is a counselor employed, less likely to encounter a student-counselor ratio of 250 to 1 or less. Further, students in urban schools also tend to have less access to counselors. Finally, the lack of access to counselors appears to be related to the wealth of the community in which the school district is located. Given the consistent findings that per pupil expenditures are much greater in wealthy districts than in not wealthy districts, access to counselors is also likely associated with the ability of the district to generate the revenue to employ counselors.

Implications and Recommendations

If school districts and the Commonwealth is serious about increasing the percentage of students graduating from high school, as well as the percentage of students graduating from high school college- and career-ready, then the Commonwealth needs to ensure that all students—but especially those most likely to benefit from having access to school counselors—have access to school counselors.

While many districts may be committed to providing counselors and ensuring a low student to counselor ratio, the lack of funding from the state legislature prohibits many districts from doing so. Indeed, appropriate access to counselors will require a legislative commitment to adequately and equitably fund all schools in the Commonwealth.

The Pennsylvania Department of Education could also include Inputs as one component of the School Performance Profile system. Specifically, two metrics could include the existence of an employed counselor in a school and the student-counselor ratio in a school.

References

- [1] American School Counselor Association. (2013). The role of the professional school counselor. Alexandria, VA: Author.

- [2] American School Counselor Association. (2013). The role of the professional school counselor. Alexandria, VA: Author.

- [3] Brown, D., Galassi, J. P., & Akos, P. (2004). School counselors’ perceptions of the impact of high-stakes testing. Professional School Counseling, 8(1), 31-39.

- [4] Winter, P. A., Keepers, B. C., Petrosko, J. P., & Ricciardi, P. D. (2005). Recruiting Teachers into a Career as School Counselor in a School Reform Environment. Planning and Changing, 36, 104–119.

- [5] White, S. W., & Kelly, F. D. (2010). The school counselor’s role in school dropout prevention. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88(2), 227–235.

- [6] Rowell, L. & Hong, E. (2015). Academic motivation: Concepts, strategies, and counseling approaches. ASCA Professional School Counselling, 16(3):1689-1699.

- [7] Davis, P., Davis, M. P., & Mobley, J. A. (2015). The school counselor’s role in addressing the advanced placement equity and excellence gap for African Americans. ASCA Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 32–39.

- [8] Rowell & Hong, (2015).

- [9] Bryan, J., Holcomb- McCoy, C., Moore-Thomas, C., & Day-Vines, N. L. (2010). Who sees the school counselor for college information? A national study. Professional School Counseling, 12, 280–291..

- [10] Bryan, Holcomb- McCoy, Moore-Thomas, & Day-Vines, (2010).

- [11] Belasco, A. S. (2013). Creating college opportunity: School counselors and their influence on postsecondary enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 54, 781–804.

- [12] Bryan, J., Moore-Thomas, C., Day-Vines, N. L., & Holcomb-McCoy, C. (2011). School counselors as social capital: The effects of high school college counseling on college application rates. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(2), 190–199.

- [13] Milsom, A., Goodnough, G., & Akos, P. (2007). School counselor contributions to the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process. Preventing School Failure, 52(1), 19–24.

- [14] Uwah, C. J., McMahon, H. G., & Furlow, C. F. (2008). School belonging, educational aspirations, and academic self-efficacy among African American male high school students: Implications for school counselors. ASCA Professional School Counselling, 11(5), 296–305.

- [15] Akos, P., & Ellis, C. M. (2008). Racial identity development in middle school: A case for school counselor individual and systemic intervention. Journal of Counseling and Development: JCD, 86(1), 26–33.

- [16] Davis, Davis, & Mobley (2015).

- [17] Nassar-McMillan, S., Karvonen, M., Perez, T. R., & Abrams, L. P. (2009). Identity development and school climate: The role of the school counselor. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education, and Development, 48(2), 195–214.

- [18] Carrell (2006).

- [19] Bryan, Moore-Thomas, Day-Vines, & Holcomb-McCoy (2011).

- [20] Lapan, R. T., Gysbers, N. C., Stanley, B., & Pierce, M. E. (2015). Missouri professional school counselors: Ratios matter, especially in high poverty schools. ASCA Professional School Counselling, 16(2), 108–116.

- [21] Carey, J., & Dimmitt, C. (2012). School counseling and student outcomes: Summary of six statewide studies. ASCA Professional School Counselling, 16(2), 146–154.

- [22] Carrell (2006).

- [23] Carrell (2006).

- [24] Pennsylvania Department of Education website located at: https://www.education.pa.gov/Data-and-Statistics/Pages/Professional-and-Support-Personnel

- Pennsylvania Department of Education School performance Profile website located at: https://paschoolperformance.org/Downloads

- [25] This measure is based on the housing market value (MV) and personal income (PI) of residents in a district. The state uses the MVPI as the official measure of district wealth.

Authors

This brief was written by Dr. Ed Fuller, Executive Director of the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy Analysis, and Diane Brenner, a graduate student in Penn State’s Department of Education Policy. Dr. Fuller can be contacted at ejf20@psu.edu+

The views contained within this brief do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Department of Education Policy Studies, the College of Education, or Penn State University.

About the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy Analysis

The mission of the CEEPA is to provide unbiased, high-quality evaluation and policy analysis services to education organizations in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and across the nation.

In addition to teaching evaluation policy and analysis courses in the College of Education, CEEPA provides evaluation and research services to schools, school districts, universities, governmental entities, and other organizations. It engages in academic leadership by publishing in the peer-reviewed literature, presenting research at state and national conferences, presenting information about evaluation research at state and national conventions, and providing evaluation services to professional organizations and scholarly journals.